|

|

|

A Resource for Athens Area Families

|

|

This common childhood illness is usually mild in kids — but it can pose a serious danger to pregnant women and their babies. Here’s what every parent needs to know.

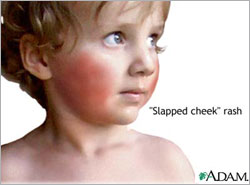

Despite its weird name, fifth disease is no big deal for most kids. But it can lead to serious, and even fatal, complications for an unborn child if the mother contracts this disease. A Common Illness The illness occurs most commonly in children. Symptoms appear between 4 and 14 days after exposure. Fifth disease causes a distinctive “slapped-cheek” rash and, less commonly, a mild fever, cold-like symptoms, headache, sore throat and joint pain. Children generally don’t get very ill. (Exceptions include children whose immune systems are compromised. In that case, contracting fifth disease can be more serious.) The illness is caused by human parvovirus B19. It got its odd name years ago when it appeared fifth in a list of what were considered the common causes of childhood rash and fever. This virus infects only humans, according to the National Institutes of Health (NIH). Dogs or cats may be immunized against "parvovirus," but these are animal parvoviruses that do not infect humans. A child can’t "catch" parvovirus from a pet, and the pet can’t catch human parvovirus B19 from a child. Infected adults often experience joint pain and swelling, are less likely to develop a rash and sometimes experience mild flu-like symptoms. About 20 percent of infected people have no symptoms, and about 60 percent of adults have had the infection in childhood, often without knowing it, according to the MOD. Currently, there is no vaccine for fifth disease. But a simple blood test can determine if someone already has been infected and, therefore, is not at risk. Treatment Options “Unfortunately, the time when they are infective is before the rash appears, which is often before the diagnosis has been made, unless there is another case (within a group of children at school or day care),” says Bostwick. This is different than for many other rash illnesses, such as measles, for which the child is contagious while he has the rash, the NIH says. Risks for Pregnant Women While such tragic outcomes aren’t common, every pregnant woman should be aware of the risks of contracting fifth disease, and should see her doctor promptly if she thinks she may have been exposed, experts say. If she was exposed to an infected person during the contagious stage of the illness (generally before the rash develops), her doctor may recommend a blood test to determine whether she has had fifth disease in the past and is immune, or if she currently has it. “Half of all women have already had fifth disease, and, therefore, they and their pregnancy would be unaffected,” says Bostwick. And most fetuses are unaffected when their mothers contract fifth disease, according to the MOD. But when a fetus does become infected, the virus can disrupt its ability to produce red blood cells, leading to a dangerous form of anemia, heart failure and up to a 9-percent risk of fetal death, with three-fourth of those cases resulting in miscarriage or stillbirth. Fetal deaths are more likely when a pregnant woman contracts the infection in the first 20 weeks of pregnancy rather than later in the pregnancy. Fifth disease in pregnancy has not been proven to cause other birth defects, according to the MOD. If a pregnant woman becomes infected with fifth disease, her doctor will monitor the pregnancy carefully for signs of fetal problems. Serious fetal complications, such as abnormal pooling of fluid around the heart, lungs or abdomen (which may result from the dangerous form of anemia mentioned earlier) can be detected through repeated ultrasound examinations. According to the MOD, most fetal complications develop by about 10 weeks after the mother was infected. If ultrasound does not show any problems during this time, no further testing is recommended. The MOD also notes that some fetuses with severe complications from parvovirus B19 infection have recovered without treatment and appear normal at birth. New Treatments on the Horizon These tests and treatments are not yet widely available, according

to the MOD. Your doctor can tell you if they are available in your

area.

|

. |

|

|

|

© 1998 - Athens Parent, Inc. All

rights reserved.

Reproduction in whole or in part without permission is prohibited. |

|

Send comments or suggestions to: webmaster@athensparent.com

|